The Art of Evil: One may smile, and smile, and be a villain…

It’s time to celebrate villains! The silver screen has given us countless big bad wolves who’ve howled and hounded our heroes, brazen with their brutality and spite. But here we’re looking at another type of evildoer, focussing on those wry, sly smilers who plot and plan behind a mask of kindness, who in the words of Shakespeare’s Richard III, are able to ‘seem a saint when most I play the devil’.

The classic chiller thriller, The Man in Black (1950), is available now, restored in 4K as part of Hammer’s Limited Collector’s Edition range. It’s a film full of treats, but it could be argued that the ‘villains of the piece’ make this movie. The almost unbearably callous Lothario, Victor, and his one-time squeeze, the arch, equally heartless Janice, are both role models of malevolence.

But the couple are rank amateurs compared to Bertha ‘I wonder if he’s going to change the will again’ Clavering. Played to icy perfection by Betty Ann Davies, she’s elegantly evil, pursuing her own ends as if the law and the lives of other people are quite unreasonable irritations. Whether she’s attempting to kill her husband or being the kind of stepmother that makes Lady Tremaine look like a loving parental figure to Cinderella, she operates with a mixture of shrewd deceit and single-minded greed. Her manipulation of Joan Clavering is typical, vacillating between waspishness and faux concern, throwing her prey off balance so the young woman can’t see the threat she so obviously poses.

‘And remember, Joan, whatever happens, you can always rely on me…’ – Bertha Clavering.

With this in mind we’ve picked out 5 villains the audience (by and large!) doesn’t see coming, or at least, didn’t see coming when the films in question were first released. Spoilers lie ahead, but even so, we’ve used headlines that reveal the movies we delve into, as opposed to the names of the miscreants who appear in them.

And to keep it interesting we’ve gone for a mixture of antagonists in order to showcase a broad range of villainy because, well, we feel it’s what Bertha would have wanted…

Mission: Impossible (1996)

These days the M:I franchise is known for its put-your-popcorn-down stunt work, glamourous global settings and, of course, Tom Cruise, Ving Rhames and Simon Pegg saving the planet on a regular basis. Oh, and Lalo Schifrin’s insanely exciting theme music.

But prior to its first big screen iteration, Mission: Impossible pretty much was team-leader Jim Phelps, played by Peter Graves. The man in charge of the IMF for all but the show’s first season, he was the face of Mission: Impossible for over one hundred episodes, reprising his role for dozens more when the series returned in the late 80s and early 90s. To the general public he was as much a part of the programme’s DNA as the words ‘should you choose accept it’ and exploding audio tape.

So when Brian De Palma directed Mission: Impossible it was inevitable Phelps would be part of the fun. But evolving the character and making him the movie’s central villain was, back then, an absolutely extraordinary move. It would be like rebooting Dad’s Army and reframing Captain Mainwaring as a Nazi agent, or resurrecting Columbo and presenting everyone’s favourite lieutenant as a drug-running assassin who simply uses the LAPD as a front.

Greg Morris (Barney Collier in the original M:I series) was so appalled by the Phelps-twist that he famously walked out of the movie’s premiere, and other stars of the TV show, including Martin Landau, were openly critical. Graves turned down a part in De Palma’s take owing to its treatment of the character he made famous. A little more philosophical than his fellow-cast members, he suggested renaming the bad guy in the film, or avoiding making Phelps a traitor ‘…by either having me in a scene in the very beginning, or reading a telegram from me saying, Hey boys, I’m retired, gone to Hawaii. Thank you, goodbye, you take over now.’ Ironically, his attempts to change the script proved to be a mission impossible and Jon Voight played Phelps as one of the most ruthless, cruel and guileful killers in the franchise’s history.

Whether you love or loathe the way Jim Phelps is portrayed in the movie, it’s a massive twist which eventually gets an emotional, positive(ish) pay-off in Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning (2025).

And Then There Were None (1945)

Any examination of films with unexpected villains must pause to applaud the more skilful adaptions of Agatha Christie’s works. The denouement of 1974’s Murder on the Orient Express (other versions are available) is a stroke of genius, but the reason why Cassetti is dispatched arguably makes his executioners something other than villainous. In Death on the Nile (1978), Poirot finally reveals that the murderer is the one person who was ostensibly an impossible suspect, and in The Mirror Crack’d (1980) an ingenious sleight of hand from the original novel works equally well in cinematic terms, providing a startling and heart-wrenching finale when the poisoner is unmasked.

But the most unexpected villain in a Christie adaption is arguably the amiable Judge Quincannon in René Clair’s And Then There Were None (1945). The way Barry Fitzgerald plays the psychopath as a helpful, practical, charismatic and at times terrified prisoner of Indian Island is a terrific disguise, and the fact that partway through the killing spree he’s pronounced dead by a doctor gives him a fairly solid alibi. It’s genuinely chilling when he pops up at the close of proceedings, totally unapologetic for his crimes and basking in his murderous achievements. Fitzgerald wisely underplays it, but his chagrin when, in his final moments, he realises he’s been outthought by two of his intended victims - although a complete deviation from Christie’s book - provides a satisfying end to Clair’s version of the mysterious ‘Mr Owen’.

‘Saint’ Vincent encounters a hitch in the form of ‘37’ (above), superbly portrayed by Melodie Simina.

37: L’Ombre et la Proie (2024)

This French movie is a fairly recent offering so we’ll try to keep spoilers to a minimum! It begins when a lorry driver, Vincent, picks up a heavily pregnant hitchhiker – always a bad move for one of the two parties in any thriller ever made. He’s ostensibly a good guy, deep in debt and struggling to do the right thing for his partner and their kids. The woman he picks up is fun and confident. Good company. Playful, even. The type of individual who seems able to glance at a person and intuitively understand them better than their closest friends. Oh, she also says her name is 37, she’s carrying a gun and casually puts on a pair of sunglasses belonging to one of Vincent’s friends. A friend who’s just been murdered…

It’s established fairly quickly that ‘37’ is a killer, and make no mistake, she’s scary as hell, determined and brutal, but as her backstory emerges the film finds more villains, with one in particular that gives the audience a ‘No, not them!’ moment. Director Arthur Môlard (who co-wrote the thriller with Claire Patronik) carefully shows that kind, decent folk can also be monsters, but there’s more nuance than this simple truism suggests. It explores how compassionate men and women can lose their way after they’ve been forced to take a couple of wrong turns. No one is immune to the possibility of it happening to them. Equally, anyone can get caught up in the horror that such misfortune can engender.

Melodie Simina delivers a thunderstorm of a performance as the eponymous slayer and 37: L’Ombre et la Proien is packed with tension, twists and some horribly effective villains. It’s well-worth taking a ride with.

A detail from the new artwork accompanying the recent release of the 4K restoration of Blood Orange.

Blood Orange (1953)

In terms of a killer we didn’t see coming, Gina in Blood Orange is hard to beat. The moment we glimpse Eric Pohlmann as Mr Mercedes we’re pretty certain he’s behind the crimes at the House of Pascal. He’s so supercilious, sadistic and openly uncaring that there’s little doubt he’s up to his homburg in skullduggery. And so it proves. Yet gradually, it becomes clear other figures are far from blameless. We never really trust Captain Colin Simpson (do we?), possibly because Tom Conway seems miffed by his popularity amongst the fashion company’s models, and partly because Andrew Osborn plays him so shadily. When he’s later described as ‘a foxy, broken-down soldier who could never make up his mind’ it strikes us as harsh but fair. Of course he’s part of the plots and duplicity that Conway is investigating.

But Gina? She’s presented as the woman our detective hero will end up with whilst the crooks and killers are being handcuffed by Detective Inspector MacLeod. She’s never too good to be true, but she seems weary of the fashion world, perhaps waiting to be rescued. Enter the Falcon! Or rather, Tom Conway, who comes across as genuinely fond of Gina. Her authentic self (‘Listen to me! I’ll take anything I want without being invited!’) is so extreme it’s appalling. Her indifference towards Helen’s possible suicide (‘Well? Did the old bag throw herself over?’) which she herself encouraged, exposes the ghastly extent of her immorality.

It’s often claimed that every villain is the hero of their own story, but ultimately, Gina knows exactly who she is. When she’s about to open a safe in order to get her hands on some classic ‘ill-gotten gains’, her companion asks if she knows the combination. Without any hint of humour she replies, ‘When I die, these figures will be written on my heart.’ The only questionable point is whether she even has one.

With her elegance, murderous sense of entitlement and unfazed acceptance of who she is, Gina comes straight from the Bertha Clavering school of villainy. We reckon they’d get on like a fashion house on fire.

Psycho (1960)

Yes, yes, yes! Now we all know that Norman Bates stands as one of cinema’s greatest villains. Complex and cunning. Straightforward and caring. Debatable, relatable and lost. A sweet young person, drowning in despair and loneliness and crushed by the burden of an overbearing loved one. We’ve all been there, right?

In terms of the bad guy we didn’t see coming, Bates works so well because for the first 25 minutes of the movie we literally don’t see him coming. Psycho is initially Marion’s film. Marion’s story. She’s presented as a hard-working person whose life never quite worked out. She’s enmeshed in a romance that’s more falling apart than falling into place. She works a job that’s okay, takes orders from a boss who’s a jerk but generally okay, and the only other woman she chats to, although delusional, is, well, okay. Yet Marion craves more than okay and when a set of random events conspire to make that a possibility, perhaps she finally recognises that she deserves better. Again, we’ve all been there, right?

She summons up the courage to finally do something about it and steals $40,000 from an objectionable man who wouldn’t notice the loss unless it was brought to his attention. To an extent she even enjoys the thrill of the theft – that smile to herself as she drives from Phoenix, recalling her crime, is a telling moment we all share with her.

Crucially, we like Marion. When that cop with the sunglasses interrogates her, we feel for her. Want her to escape. We get the sense that if she could go back in time and deposit the cash in the bank, she’d do it in a heartbeat. So the motel stop is, ostensibly at least, simply the next beat of her story and the interesting young man she meets is apparently a catalyst for her to understand that one mistake doesn’t have to destroy everything.

After all, as Norman points out, ‘We all go a little mad sometimes.’

As set-ups go, it’s near perfect and the first murder we see Norman commit is now so famous, so shocking, so palpable, not simply because of Janet Leigh’s extraordinary performance and Hitchcock’s masterful direction and editing, but because of the misdirect that precedes it.

A behind-the-scenes publicity shot of Anthony Perkins who played Norman Bates in four Psycho movies.

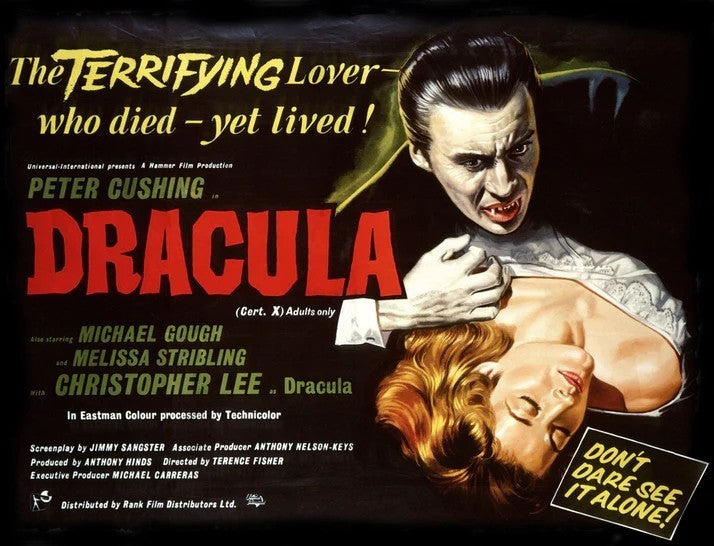

The moment we finally see Norman as the murderous mother/son hybrid he created, is perhaps even more horrific than the shower scene. It’s the first time we truly take in the real killer whose presence has pervaded the film since, through the darkness and driving rain, Marion spotted the signage for the Bates Motel. Like Dracula in the first Hammer movie to feature the Count, or Doctor Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), or even Harry Lime in The Third Man (1949), we spend very little time with the tale’s infamous antagonist. And as with all those characters, the scarcity of their screentime makes their presence more keenly felt when it arrives.

Alfred Hitchcock once noted, ‘The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture.’ And he brought some corkers to life: Mrs Danvers in Rebecca (1940), Brandon Shaw in Rope (1948), Anna Sebastian and her son in Notorious (1946) and Bob Rusk in Frenzy (1972) are all royalty amongst rogues, but as compelling, endlessly fascinating villains go, Norman Bates is a cut above the rest.

Marketing material for Hammer’s The Nanny, directed by Seth Holt and starring, as seen in this image, the legendary Bette Davis.

Honourable mentions to the following…

Many more reprobates could be added to this list, but we felt a hat tip to a few who didn’t quite make our top 5 was in order…

Blumhouse’s Drop (2025) slyly suggests a twist which horror / thriller aficionados will invariably seize upon, before subverting the resultant expectation with a final reveal that feels startling but completely earned. Writing for Inverse, Hoai-Tran Bui called the work, ‘…a fun, efficient little thriller’ and undoubtedly, part of its success comes from the identity of the person behind the murders and mischief.

And on the subject of identity… Director James Mangold called his mystery movie, Identity (2003) ‘…this kind of noir And Then There Were None amped up to eleven on the volume knob…’ It’s a fair summation. During a screening for critics, on-site problems meant the film had to be paused for several minutes. The critics got together during the break and speculated which character would emerge as the movie’s villain. It’s a testament to the originality of Identity that not a single one of the experts nailed the solution – which we’re not about to spoil! Be warned though, the thriller’s conclusion divided audiences, but in terms of a twist antagonist, it’s undeniably right up there.

Finally, Hammer remains famous for many of its glorious villains, including the eponymous ghoul in The Nanny (1965), Count Dracula in several pictures, Ingrid Pitt’s Carmilla in The Vampire Lovers (1970), and the ship of sinners in The Mystery of the Mary Celeste (1936). It’s also given us a few unexpected guilty parties, from the sublime, such as the murderer in Death in High Heels (1947), to the ridiculous. And yes, loveable George Roper in Man About the House (1974), we’re looking at you!

The Man in Black and Blood Orange are available now as part of Hammer’s ongoing Limited Collector’s Edition range. You can find both titles, along with many more films and related merchandise, at the official online shop.